Monday, June 29, 2009

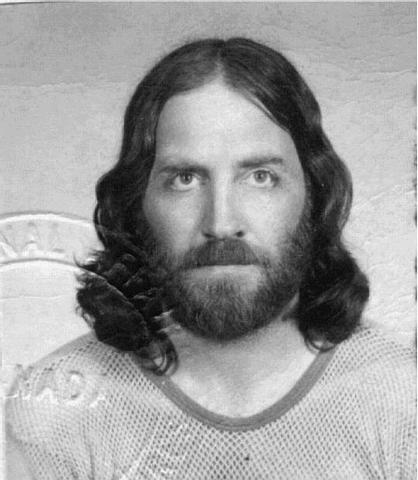

Paul Beingesner Obituary

PAUL JOSEPH BEINGESSNER of Truax, Saskatchewan, passed away suddenly on June 25, 2009 at the age of 55 years. Paul was born April 26, 1954 in Moose Jaw and spent most of his life on the family farm at Truax. He is predeceased by his father, Herbert, and survived by his mother, Agnes, his wife Faye, his sisters Dolores (Ken), Rita (Bill), Cathy (Lawrence), and Virginia, his children Naomi (Dan), Chris (Brenda), Kate, and their mother Laura, and his sons James (Carolyn), and David. He doted on his grandchildren, Vincent, Norah and Edith. After getting a B.A. (Hon) in Psychology from the University of Regina in 1976, he worked with at-risk youth at the Roy Wilson Centre in Sedley. The patience and compassion he exhibited with these youth characterized all of his interactions with people and animals throughout his life. Returning to the farm full-time in 1981, Paul farmed alongside his father and raised grain, cattle, chickens, turkeys and a formidable army of cats. Never one to sit idly, in addition to farming Paul served as a Saskatchewan Wheat Pool Delegate from 1996 to 1998. He was instrumental in the founding of Saskatchewan's first short-line railway, Southern Rails Co-operative, and served as general manager from 1991 to 1997. When he left Southern Rails, he stayed on as a board member, and worked with the Ministry of Highways Short Line Advisory Unit supporting other efforts of farmers to start short-line railways. Since 1991, Paul wrote a weekly column on farming and transportation issues with a social justice focus featured in papers across Western Canada. After leaving the government in 1999, his expertise on transportation issues resulted in consulting work across Western Canada and the United States, which he continued up until his untimely passing. He was named an honorary lifetime member of the Saskatchewan Institute of Agrologists in 2008. Though he was active with his work off the farm, his true passion was farming, the land, and community. He loved everything to do with the outdoors hunting, bird-watching, camping, gardening, and searching for rocks with fossils while walking countless miles of railroad track and fence. Paul's compassion stretched to all living things; he often doctored sick cats, lambs, and even wildlife he came across, in an effort to save a life. He loved to organize drama for the children in the area and produced an annual Christmas play with them that brought the community together. Paul was thirsty for knowledge, and there was hardly anything that he couldn't do or wouldn't try. If he didn't know how to do something, he would find out. No matter how serious life and politics became, Paul never lost his trademark sense of humour; it was a pleasure to endure his teasing or fall victim to one of his practical jokes. Above all, Paul was a man of faith, and served as a liturgical coordinator in his parish. Vigil for Paul will be held at 7:30 pm on Wednesday, July 1st at St. Anne's Catholic Parish in Truax, Saskatchewan. A Funeral Mass celebrating his life will be held at 1:00 p.m. on Thursday, July 2nd, at St. Joseph's Catholic Parish in Claybank. Interment will follow at the Truax CemeteryCatholic Section. In lieu of flowers, donations in Paul's memory can be made to Amnesty International or Development and Peace.

Friday, June 26, 2009

A Terrible Loss to All of Us

I was imformed today by Faye Beingesner of the tragic death of her husband Paul in an agricultural accident on June 25. The article below is his last. It seems to me in character of this great caring man that his last two articles were of the plight of the worlds impoverished and starving peoples.

At this time I'm unable to write more since I'm full of an immense sorrow, and anger, that such a towering figure is lost to us all. He will be sorely missed.

Little Muddy

At this time I'm unable to write more since I'm full of an immense sorrow, and anger, that such a towering figure is lost to us all. He will be sorely missed.

Little Muddy

First World Economic Policies Increase Hunger

Column # 725 22/06/09

The World Food Program, an agency of the United Nations, announced

last week that the number of hungry people in the world rose this year

to over one billion. It is a startling number. It says that, though

the world continues to grow richer in many senses and for many people,

it is growing poorer at supplying more of its citizens with food. This

is not the way it was supposed to be, not the way it was from 1990 to

2005. In that time period, poverty (extreme poverty) in developing

countries fell steadily. Around 2005, this reversed, and poverty, and

with it hunger, began to rise again. This has continued unabated.

The large increase in hunger in the first half of 2009 has been blamed

by the World Food Program on continuing high food prices, but it has

been much longer in the making than the commodity boom that arose from

the banking crisis in the U.S. last year. Like the market crash and

sub-prime mortgage mess, hunger in poor countries has been caused in

many cases by actions taken in rich ones.

Until recently, international agencies like the World Bank, the

International Monetary Fund and the U.S. Treasury Department promoted

policies that came to be known as the Washington Consensus. These

policies became requirements for countries that wanted loans from the

World Bank and IMF. The American government and governments in Europe

also demanded that countries wanting to receive aid follow the

prescriptions of the Washington Consensus. Key among these were trade

liberalization, privatization of state enterprises and deregulation.

One of the results of the Washington Consensus was that spending on

agriculture by poor countries declined. This was often demanded as a

condition for aid and loans. Meanwhile, the amount of money given by

rich countries for the development of agriculture in poor countries

also declined. While imposing these restrictions on underdeveloped

nations, the U.S. and the European Union continued to provide ample

subsidies to their own agriculture sectors. It was fully expected that

poor countries would be able to buy their food needs on international

markets while switching their economies over to export oriented

agriculture and industries. They would export flowers to us and we

would export food to them.

The result was that the food producing capacity of many poor countries

declined. Agricultural research and infrastructure were neglected and

subsistence farmers were pushed aside for oilseed plantations and

other export crops.

In 2007/2008, food prices began to rise as a long period of declining

food stocks world-wide suddenly got noticed. On top of that, the

economic collapse in many developed countries reduced markets for the

production of the poor. They could no longer afford to eat.

Some world governments continue to prescribe more of the same as the

cure for hunger and poverty - more trade, more deregulation and more

privatization. But here is the odd thing. Two of the largest and

poorest countries in the world have reduced poverty to a greater

extent than any, and they did it while violating most of the

principles of the Washington Consensus. I'm talking, of course, about

India and China. Both countries resisted privatization of government

services, continued to protect their own economies with tariffs and

did not make deregulation the be-all-and-end-all of political policy.

So what's to be done? We have rapidly increasing hunger at a time when

rich countries are preoccupied with their own economic troubles, like

whether we'll be able to keep all the Hummers on the road. With

troubles like that, how will they have time to think about the hungry

in far-off lands?

Various international agencies have proposed some solutions. These

include

* Increasing aid to agriculture in poor countries and targeting it at

appropriate production that will meet the needs of rural and urban

poor.

* Building food reserves, like India and China did, that can be

released at times when supply is low and prices high. This will

prevent price volatility.

* Tighten regulations on stock exchanges that trade in commodities to

prevent excessive speculation.

* Negotiate trade agreements that allow poor countries to protect

their economies in times of crisis and exploitation.

* Control the market power of massive corporations that can cause

markets to swing on their whim.

Of course these measures run counter to the laissez-faire economic

policies promoted by the world's major powers. But in the current

economic crisis, they are precisely what is needed. Having caused the

problem to a great extent with the failed policies of the Washington

Consensus, rich nations bear some responsibility toward the poor.

In the short term we need to alleviate the hunger that is pressing

down on one billion people. Nor is the cost significant compared to

what we are currently showering on our own economies. Less than one

percent of the global stimulus package would fund the current deficit

in the World Food Program.

We should not underestimate the value of living in a world where

hunger is eliminated. As someone pointed out, any country is only four

missed meals away from anarchy. And anarchy that strikes in one

country often has ramifications for another half a world away.

© Paul Beingessner beingessner@sasktel.net

The World Food Program, an agency of the United Nations, announced

last week that the number of hungry people in the world rose this year

to over one billion. It is a startling number. It says that, though

the world continues to grow richer in many senses and for many people,

it is growing poorer at supplying more of its citizens with food. This

is not the way it was supposed to be, not the way it was from 1990 to

2005. In that time period, poverty (extreme poverty) in developing

countries fell steadily. Around 2005, this reversed, and poverty, and

with it hunger, began to rise again. This has continued unabated.

The large increase in hunger in the first half of 2009 has been blamed

by the World Food Program on continuing high food prices, but it has

been much longer in the making than the commodity boom that arose from

the banking crisis in the U.S. last year. Like the market crash and

sub-prime mortgage mess, hunger in poor countries has been caused in

many cases by actions taken in rich ones.

Until recently, international agencies like the World Bank, the

International Monetary Fund and the U.S. Treasury Department promoted

policies that came to be known as the Washington Consensus. These

policies became requirements for countries that wanted loans from the

World Bank and IMF. The American government and governments in Europe

also demanded that countries wanting to receive aid follow the

prescriptions of the Washington Consensus. Key among these were trade

liberalization, privatization of state enterprises and deregulation.

One of the results of the Washington Consensus was that spending on

agriculture by poor countries declined. This was often demanded as a

condition for aid and loans. Meanwhile, the amount of money given by

rich countries for the development of agriculture in poor countries

also declined. While imposing these restrictions on underdeveloped

nations, the U.S. and the European Union continued to provide ample

subsidies to their own agriculture sectors. It was fully expected that

poor countries would be able to buy their food needs on international

markets while switching their economies over to export oriented

agriculture and industries. They would export flowers to us and we

would export food to them.

The result was that the food producing capacity of many poor countries

declined. Agricultural research and infrastructure were neglected and

subsistence farmers were pushed aside for oilseed plantations and

other export crops.

In 2007/2008, food prices began to rise as a long period of declining

food stocks world-wide suddenly got noticed. On top of that, the

economic collapse in many developed countries reduced markets for the

production of the poor. They could no longer afford to eat.

Some world governments continue to prescribe more of the same as the

cure for hunger and poverty - more trade, more deregulation and more

privatization. But here is the odd thing. Two of the largest and

poorest countries in the world have reduced poverty to a greater

extent than any, and they did it while violating most of the

principles of the Washington Consensus. I'm talking, of course, about

India and China. Both countries resisted privatization of government

services, continued to protect their own economies with tariffs and

did not make deregulation the be-all-and-end-all of political policy.

So what's to be done? We have rapidly increasing hunger at a time when

rich countries are preoccupied with their own economic troubles, like

whether we'll be able to keep all the Hummers on the road. With

troubles like that, how will they have time to think about the hungry

in far-off lands?

Various international agencies have proposed some solutions. These

include

* Increasing aid to agriculture in poor countries and targeting it at

appropriate production that will meet the needs of rural and urban

poor.

* Building food reserves, like India and China did, that can be

released at times when supply is low and prices high. This will

prevent price volatility.

* Tighten regulations on stock exchanges that trade in commodities to

prevent excessive speculation.

* Negotiate trade agreements that allow poor countries to protect

their economies in times of crisis and exploitation.

* Control the market power of massive corporations that can cause

markets to swing on their whim.

Of course these measures run counter to the laissez-faire economic

policies promoted by the world's major powers. But in the current

economic crisis, they are precisely what is needed. Having caused the

problem to a great extent with the failed policies of the Washington

Consensus, rich nations bear some responsibility toward the poor.

In the short term we need to alleviate the hunger that is pressing

down on one billion people. Nor is the cost significant compared to

what we are currently showering on our own economies. Less than one

percent of the global stimulus package would fund the current deficit

in the World Food Program.

We should not underestimate the value of living in a world where

hunger is eliminated. As someone pointed out, any country is only four

missed meals away from anarchy. And anarchy that strikes in one

country often has ramifications for another half a world away.

© Paul Beingessner beingessner@sasktel.net

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Cheap Food Not Much of an Answer

Column # 724 15/06/09

I recently saw a story about farmers reducing fertilizer use, in response to high prices. The story warned that this was dangerous, as farmers should not be reducing inputs in an age of food shortages. It went on to argue that farmers will benefit from maximizing production. Another news report the same day pointed out that the food crisis was far from over, despite being overshadowed by the world economic crisis. While farm products have declined in value, they are still priced beyond what many in poor countries can afford. As if to reinforce the point, we are now being told that the number of malnourished citizens of Earth has topped one billion.

While the American Declaration of Independence may have declared that all men are created equal, the same can no longer be said of all hungry people. The hungry, it seems, can be divided into two classes - those with money and those without. That you can be hungry without money is self-explanatory. But being hungry with money requires some elaboration. It is the fate, or at least the fate they anticipate for themselves, of people who don't have enough arable land or perhaps water to grow sufficient food for their needs. The obvious examples are the Arab Gulf states, swimming in oil but singularly lacking water. Saudi Arabia, for example, used to grow a great deal of barley and wheat. It stopped doing that when it became apparent it would thereby consume all its fresh water. Other countries in the same boat include Japan and China.

Wealthy but hungry countries have a solution to their problems. They are buying land in poor countries that are willing to sell or lease land to produce food, which then belongs to the wealthy country, or at least to the company that represents that country. A ludicrous example of this is Sudan, a country that relies on food aid to feed its people, but which is willing to allow its land to be taken over and food to be exported.

In the end, this technique simply takes food out of international markets, and will likely result in lower prices for all foods, as demand is reduced in importing countries. Prices to the farmer will decline, and this will undoubtedly be seen as positive by folks concerned with world hunger.

You don't need to be a farmer, with a whole lot of skin in the wringer, to see that this isn't a good thing.(It does help, though.) Farmers, the few that remain, know full well they do not receive enough for their products to make farming sustainable over the long run. They also know the conundrum food producers and consumers face. Without more money, farmers will reduce fertilizer use, limit other inputs, and production will fall.

The result will be catastrophic for poor people. So, what to do?

First of all, international agencies and governments should quit using the simple argument that food prices are too high. Opponents of ethanol argue, for example, that using feed grains to produce ethanol has raised the price of food in the U.S. and around the world. This, apparently, is a strike against ethanol.

Bad argument. (There are lots better ones to use.) What it says is that farmers should produce cheap food. That is the way to combat hunger. As I argued earlier, farmers can't and won't produce crops for inadequate returns forever. That ethanol production is a better deal for farmers than selling to food markets is simply an indictment of the international economic system.

Those who care about the hungry should be glad for higher food prices in one sense. These ought to insure farmers will continue to produce food. The real question is not how high food prices should be. They should be high enough to ensure farmers a reasonable living. The real question is, how will the hungry be fed? That leads to a different set of answers than simply eliminating the things that keep food prices high.

Now, to head off the critics I can already hear in my head, let me be clear that I don't think higher crop prices necessarily lead to more income for farmers. In most cases, that greater value is simply eaten up by input makers and service providers. Just as those concerned with the poor need to reframe the question of how people will be fed, farmers and politicians need to reframe the question of how farmers can be sustained. Good prices alone will not do it, in a system when market power is concentrated in a few hands. The temptation is to forget this when times are good. Times will not be good forever.

© Paul Beingessner beingessner@sasktel.net

I recently saw a story about farmers reducing fertilizer use, in response to high prices. The story warned that this was dangerous, as farmers should not be reducing inputs in an age of food shortages. It went on to argue that farmers will benefit from maximizing production. Another news report the same day pointed out that the food crisis was far from over, despite being overshadowed by the world economic crisis. While farm products have declined in value, they are still priced beyond what many in poor countries can afford. As if to reinforce the point, we are now being told that the number of malnourished citizens of Earth has topped one billion.

While the American Declaration of Independence may have declared that all men are created equal, the same can no longer be said of all hungry people. The hungry, it seems, can be divided into two classes - those with money and those without. That you can be hungry without money is self-explanatory. But being hungry with money requires some elaboration. It is the fate, or at least the fate they anticipate for themselves, of people who don't have enough arable land or perhaps water to grow sufficient food for their needs. The obvious examples are the Arab Gulf states, swimming in oil but singularly lacking water. Saudi Arabia, for example, used to grow a great deal of barley and wheat. It stopped doing that when it became apparent it would thereby consume all its fresh water. Other countries in the same boat include Japan and China.

Wealthy but hungry countries have a solution to their problems. They are buying land in poor countries that are willing to sell or lease land to produce food, which then belongs to the wealthy country, or at least to the company that represents that country. A ludicrous example of this is Sudan, a country that relies on food aid to feed its people, but which is willing to allow its land to be taken over and food to be exported.

In the end, this technique simply takes food out of international markets, and will likely result in lower prices for all foods, as demand is reduced in importing countries. Prices to the farmer will decline, and this will undoubtedly be seen as positive by folks concerned with world hunger.

You don't need to be a farmer, with a whole lot of skin in the wringer, to see that this isn't a good thing.(It does help, though.) Farmers, the few that remain, know full well they do not receive enough for their products to make farming sustainable over the long run. They also know the conundrum food producers and consumers face. Without more money, farmers will reduce fertilizer use, limit other inputs, and production will fall.

The result will be catastrophic for poor people. So, what to do?

First of all, international agencies and governments should quit using the simple argument that food prices are too high. Opponents of ethanol argue, for example, that using feed grains to produce ethanol has raised the price of food in the U.S. and around the world. This, apparently, is a strike against ethanol.

Bad argument. (There are lots better ones to use.) What it says is that farmers should produce cheap food. That is the way to combat hunger. As I argued earlier, farmers can't and won't produce crops for inadequate returns forever. That ethanol production is a better deal for farmers than selling to food markets is simply an indictment of the international economic system.

Those who care about the hungry should be glad for higher food prices in one sense. These ought to insure farmers will continue to produce food. The real question is not how high food prices should be. They should be high enough to ensure farmers a reasonable living. The real question is, how will the hungry be fed? That leads to a different set of answers than simply eliminating the things that keep food prices high.

Now, to head off the critics I can already hear in my head, let me be clear that I don't think higher crop prices necessarily lead to more income for farmers. In most cases, that greater value is simply eaten up by input makers and service providers. Just as those concerned with the poor need to reframe the question of how people will be fed, farmers and politicians need to reframe the question of how farmers can be sustained. Good prices alone will not do it, in a system when market power is concentrated in a few hands. The temptation is to forget this when times are good. Times will not be good forever.

© Paul Beingessner beingessner@sasktel.net

Monday, June 08, 2009

Rushing Madly Off in All Directions

Column # 723 08/06/09

When mad cow disease hit western Canada in May, 2003, farmers got a

lesson in basic economics. The lesson wasn't so much that prices went

down in Canada. Take away the market for something like 50 percent of

the cattle produced in Canada, and prices will take a gut-wrenching

tumble. That was a given.

The real lesson came in what happened in the United States. Canadian

beef constituted a small amount of the beef consumed in the U.S.,

something less than 3 percent. To Canada, obviously, the amount was

huge. To the U.S., not so much. But cattle prices in the U.S.

skyrocketed. Farmers were getting record high prices for their calves,

and this continued for some time. The lesson was in the major impact a

small change in supply could have on a market fairly well balanced.

It is a lesson that has apparently been forgotten (if it was ever

learned) by some Canadian grain producers. These are the people

moaning that prices for durum wheat at elevators in the United States

in the 2008/09 crop year have been higher than the CWB Pool Return

Outlook for durum western Canada. So we have the vice-president of the

Western Canadian Wheat Growers berating the CWB, claiming it is

"costing farmers a bundle".

No doubt there is such a thing as willful ignorance, but it is hard to

believe that Stephen Vandervalk actually believes his own rhetoric. He

should know, for example, that the CWB sells only a small proportion

of western Canadian durum to the United States in any given year. This

crop year, the U.S. has taken about one-sixth of our durum. The entire

U.S. durum market amounts to about half of our production. So if

Vandervalk could have his way, and start madly trucking his durum

across the border to those American elevators, and if all, or even a

significant number of Canadian farmers did the same, it would be mad

cow in reverse. The huge increase in supply would cause prices to

crash faster than you could say, "Geez, how dumb was that?"

Of course, comparing American elevator prices to the pooled CWB price

is screwy logic to begin with. Five-sixths of our durum goes to

countries other than the U.S. Freight costs to get it there are much

higher, involving both domestic rail and ocean shipping. Countries

like Morocco and Algeria typically don't pay what richer countries do,

so the pooled price reflects a mix of these low and high prices.

To top it off, the CWB has been selling to the U.S. at prices that are

higher than the elevator prices Vandervalk is so determined he could

get. If he had his way, and crashed the U.S. price, everyone would be

a loser.

The other major complaint from the Wheat Growers is that the CWB has

not taken all the durum farmers have grown. This crop year, it will be

about 80 percent. This reflects that fact that the market for durum

worldwide is finite. Humans only consume so much pasta, couscous,

chapati and bulgar. Push more durum onto world markets than the world

will consume and it will be sold at feed prices. The problem with this

is that durum customers will see durum selling as feed and will reduce

their expectations of what they must pay.

American farmers should actually be quite happy with the CWB. By

refusing to flood world markets with cheap durum, it has held the

price up for farmers on both sides of the border. In a completely open

market, price signals for planting durum would come from the dropping

prices as farmers pushed too much durum onto the market. With the CWB,

the price signal is the fact that we can't sell all our production.

Farmers in my area know this. Durum has been a profitable crop with

price premiums over red spring wheat virtually every year. But we also

know we can't plant every acre to durum. In the case of durum, the

Wheat Growers seem to lack fundamental understanding of how markets

work.

© Paul Beingessner beingessner@sasktel.net

When mad cow disease hit western Canada in May, 2003, farmers got a

lesson in basic economics. The lesson wasn't so much that prices went

down in Canada. Take away the market for something like 50 percent of

the cattle produced in Canada, and prices will take a gut-wrenching

tumble. That was a given.

The real lesson came in what happened in the United States. Canadian

beef constituted a small amount of the beef consumed in the U.S.,

something less than 3 percent. To Canada, obviously, the amount was

huge. To the U.S., not so much. But cattle prices in the U.S.

skyrocketed. Farmers were getting record high prices for their calves,

and this continued for some time. The lesson was in the major impact a

small change in supply could have on a market fairly well balanced.

It is a lesson that has apparently been forgotten (if it was ever

learned) by some Canadian grain producers. These are the people

moaning that prices for durum wheat at elevators in the United States

in the 2008/09 crop year have been higher than the CWB Pool Return

Outlook for durum western Canada. So we have the vice-president of the

Western Canadian Wheat Growers berating the CWB, claiming it is

"costing farmers a bundle".

No doubt there is such a thing as willful ignorance, but it is hard to

believe that Stephen Vandervalk actually believes his own rhetoric. He

should know, for example, that the CWB sells only a small proportion

of western Canadian durum to the United States in any given year. This

crop year, the U.S. has taken about one-sixth of our durum. The entire

U.S. durum market amounts to about half of our production. So if

Vandervalk could have his way, and start madly trucking his durum

across the border to those American elevators, and if all, or even a

significant number of Canadian farmers did the same, it would be mad

cow in reverse. The huge increase in supply would cause prices to

crash faster than you could say, "Geez, how dumb was that?"

Of course, comparing American elevator prices to the pooled CWB price

is screwy logic to begin with. Five-sixths of our durum goes to

countries other than the U.S. Freight costs to get it there are much

higher, involving both domestic rail and ocean shipping. Countries

like Morocco and Algeria typically don't pay what richer countries do,

so the pooled price reflects a mix of these low and high prices.

To top it off, the CWB has been selling to the U.S. at prices that are

higher than the elevator prices Vandervalk is so determined he could

get. If he had his way, and crashed the U.S. price, everyone would be

a loser.

The other major complaint from the Wheat Growers is that the CWB has

not taken all the durum farmers have grown. This crop year, it will be

about 80 percent. This reflects that fact that the market for durum

worldwide is finite. Humans only consume so much pasta, couscous,

chapati and bulgar. Push more durum onto world markets than the world

will consume and it will be sold at feed prices. The problem with this

is that durum customers will see durum selling as feed and will reduce

their expectations of what they must pay.

American farmers should actually be quite happy with the CWB. By

refusing to flood world markets with cheap durum, it has held the

price up for farmers on both sides of the border. In a completely open

market, price signals for planting durum would come from the dropping

prices as farmers pushed too much durum onto the market. With the CWB,

the price signal is the fact that we can't sell all our production.

Farmers in my area know this. Durum has been a profitable crop with

price premiums over red spring wheat virtually every year. But we also

know we can't plant every acre to durum. In the case of durum, the

Wheat Growers seem to lack fundamental understanding of how markets

work.

© Paul Beingessner beingessner@sasktel.net

Monday, June 01, 2009

Potential to Profit From Pollution

Column # 722 01/06/09

A lot of farmers don't really believe in global warming. Or, if you push them on it a bit, they don't believe humans are responsible for global warming. The warming of the earth itself is hard to deny when robins are seen north of the Arctic Circle and polar ice is melting at an unprecedented rate.

I'm no expert on climate, but you can't doubt that, despite the cool spring we are experiencing, the climate is getting warmer. This is particularly true in polar regions, which is what the models predict. And the speed of the changes in this area makes it difficult to believe it is just a normal cycle. Unless you have a massive volcano somewhere on earth, natural forces just don't act this fast.

All that aside, the global scientific community overwhelmingly believes that burning fossil fuels is the major cause of global warming, that its effects are irreversible in our lifetimes, and that they will not be a good thing. Governments around the world have been convinced by this as well, and there are international initiatives claiming to try to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases.

Coupled with the problem of global warming is the issue of declining stocks of oil and gas. In many ways they are two heads of the same monster. As hugely populated countries like China and India increase their standard of living, and as people in rich countries like Canada build bigger houses and drive more and bigger cars, use of fossil fuels is increasing dramatically each year. Most scientists agree we are reaching a point where production of conventional oil will not keep up with demand. The situation is even more critical with natural gas, despite new sources such as coalbed methane. Natural gas demand in Canada is increasing quickly, mostly for production of oil from the tar sands.

So, if you believe humans are responsible for global warming, or if you worry about the eventual real shortages of fossil fuels, it makes sense to reduce consumption of oil, gas and other non-renewable forms of energy.

Reduction of greenhouse gases has become a priority for governments – at least in terms of lip service. The reality is something different, as most governments, including ours, continually weaken and push back targets. However, the issue is not going away, and governments will continue to be pressured by the public and the scientific community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Enter the cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions. (Carbon dioxide is a major greenhouse gas.) This concept says governments should introduce a cap on total emissions, then allow emitters to trade in a market for permits to pollute. So if a company wants to increase its emissions of carbon dioxide by, for example, opening up a new tar sand development, it would have to find someone who is willing to reduce their emissions, and then buy these surplus emission "credits".

Farmers and farm groups like the Canadian Federation of Agriculture have been quick to jump on this carbon credit bandwagon. Some agricultural practices have the ability to take carbon dioxide from the air and sequester it in the soil. Converting cropland to grassland is a good example. Of course, if the grass is re-broken, much of the carbon is again given off to the atmosphere. Agriculture is, in fact, all about taking and giving of carbon. Plants take carbon dioxide from the air to form their cellular structure, then release it again as the plant decays.

When farmers discuss carbon sequestration it is seldom about decreasing global warming. It is usually in the context of getting some money into the hands of farmers. Farmers argue that current practices like reduced tillage sequester more carbon so farmers should benefit from providing this "service" to society.

The problem with cap-and-trade is that it largely looks like a shell game. Farmers have adopted reduced tillage systems because they worked to improve the bottom line, not to reduce greenhouse gases. With or without a carbon market, they will not change what they are doing. For a company to then purchase carbon credits from farmers makes no real difference to what would happen anyway as far as the farmer is concerned. For the polluter, it is a low-cost license to pollute. You can't blame farmers for wanting to cash in – it appears everyone wants to cash in somehow. But to reduce greenhouse gases and stretch out the life of our oil supplies we need to reduce consumption.

In this regard, farmers can do a lot. We are major users of fossil fuels and there are many ways we can reduce this. I recently had a conversation with a farmer about energy use. He admitted that in winter you could readily find three tractors idling on their farm, even with only two operators around. They just don't like getting into a cold tractor, he told me.

Farmers can get an energy audit done for their farm. This is a real eye-opener and can show lots of ways to reduce energy consumption, and hence save money. This will have a greater effect on the bottom line than selling a carbon credit for something you do anyway. It will also have a real effect on greenhouse gas production, not just give the illusion something is being done.

© Paul Beingessner beingessner@sasktel.net

A lot of farmers don't really believe in global warming. Or, if you push them on it a bit, they don't believe humans are responsible for global warming. The warming of the earth itself is hard to deny when robins are seen north of the Arctic Circle and polar ice is melting at an unprecedented rate.

I'm no expert on climate, but you can't doubt that, despite the cool spring we are experiencing, the climate is getting warmer. This is particularly true in polar regions, which is what the models predict. And the speed of the changes in this area makes it difficult to believe it is just a normal cycle. Unless you have a massive volcano somewhere on earth, natural forces just don't act this fast.

All that aside, the global scientific community overwhelmingly believes that burning fossil fuels is the major cause of global warming, that its effects are irreversible in our lifetimes, and that they will not be a good thing. Governments around the world have been convinced by this as well, and there are international initiatives claiming to try to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases.

Coupled with the problem of global warming is the issue of declining stocks of oil and gas. In many ways they are two heads of the same monster. As hugely populated countries like China and India increase their standard of living, and as people in rich countries like Canada build bigger houses and drive more and bigger cars, use of fossil fuels is increasing dramatically each year. Most scientists agree we are reaching a point where production of conventional oil will not keep up with demand. The situation is even more critical with natural gas, despite new sources such as coalbed methane. Natural gas demand in Canada is increasing quickly, mostly for production of oil from the tar sands.

So, if you believe humans are responsible for global warming, or if you worry about the eventual real shortages of fossil fuels, it makes sense to reduce consumption of oil, gas and other non-renewable forms of energy.

Reduction of greenhouse gases has become a priority for governments – at least in terms of lip service. The reality is something different, as most governments, including ours, continually weaken and push back targets. However, the issue is not going away, and governments will continue to be pressured by the public and the scientific community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Enter the cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions. (Carbon dioxide is a major greenhouse gas.) This concept says governments should introduce a cap on total emissions, then allow emitters to trade in a market for permits to pollute. So if a company wants to increase its emissions of carbon dioxide by, for example, opening up a new tar sand development, it would have to find someone who is willing to reduce their emissions, and then buy these surplus emission "credits".

Farmers and farm groups like the Canadian Federation of Agriculture have been quick to jump on this carbon credit bandwagon. Some agricultural practices have the ability to take carbon dioxide from the air and sequester it in the soil. Converting cropland to grassland is a good example. Of course, if the grass is re-broken, much of the carbon is again given off to the atmosphere. Agriculture is, in fact, all about taking and giving of carbon. Plants take carbon dioxide from the air to form their cellular structure, then release it again as the plant decays.

When farmers discuss carbon sequestration it is seldom about decreasing global warming. It is usually in the context of getting some money into the hands of farmers. Farmers argue that current practices like reduced tillage sequester more carbon so farmers should benefit from providing this "service" to society.

The problem with cap-and-trade is that it largely looks like a shell game. Farmers have adopted reduced tillage systems because they worked to improve the bottom line, not to reduce greenhouse gases. With or without a carbon market, they will not change what they are doing. For a company to then purchase carbon credits from farmers makes no real difference to what would happen anyway as far as the farmer is concerned. For the polluter, it is a low-cost license to pollute. You can't blame farmers for wanting to cash in – it appears everyone wants to cash in somehow. But to reduce greenhouse gases and stretch out the life of our oil supplies we need to reduce consumption.

In this regard, farmers can do a lot. We are major users of fossil fuels and there are many ways we can reduce this. I recently had a conversation with a farmer about energy use. He admitted that in winter you could readily find three tractors idling on their farm, even with only two operators around. They just don't like getting into a cold tractor, he told me.

Farmers can get an energy audit done for their farm. This is a real eye-opener and can show lots of ways to reduce energy consumption, and hence save money. This will have a greater effect on the bottom line than selling a carbon credit for something you do anyway. It will also have a real effect on greenhouse gas production, not just give the illusion something is being done.

© Paul Beingessner beingessner@sasktel.net

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)